This paper will concern itself with three teaching techniques for the classical classroom. These three have been selected because they are easy to learn – but difficult to master; they can implemented in all age groups from K to 12. They can be used in almost every subject area. They are high impact: high impact for the students but also high impact for the teacher, in opening one’s eyes to a different way of teaching.

This entry is Part Three of a three-part article. Visit these links for Part One and Part Two.

The Renaissance

One of the great sayings of this period was Ad Fontes – meaning "To the Source” or “Wellspring”. This term carries some controversy for its use in the Reformation and Counter-Reformation, which I don’t want to necessarily get into; rather I’d like to focus on the work and dispositions of these figures, who are found across the Protestant and Catholic divide, whose work in literature, poetry, humanist philosophy all had a reverence for the past and looked back to the sources and wellspring of the classical world that had become once again accessible to European kingdoms in this era. This was not done in a crude nostalgia for the classical world, to blindly recreate it anew, but in order to bring old treasures to new appreciation in their own time.

- The poets and dramatists - Shakespeare, Dante, Petrarch.

- Humanist reformers and educational thinkers - Erasmus, Philip Melanchthon.

- Statesman like Thomas More or moral visionaries Christine de Pizan.

I believe they all held this principle highly which I want to introduce to you.

The principle is:

Enter the Great Conversation with Courage and Humility.

And what I mean by "the Great Conversation" I will hopefully be able bring out in relation to this technique or what you might also call a disposition.

Choosing Primary Sources and Classic Texts

I am not against using textbooks to teach history but I am against not using primary sources. After all the historical task, is forming that narrative that we call history, a history is not a chronicle, it is not a series of events with no relation. And so our students must come to bear with primary sources if we hope to engender in them an appreciation of the historical task, of the distance of history, its preciousness. As it turns out this is a lot more fun too.

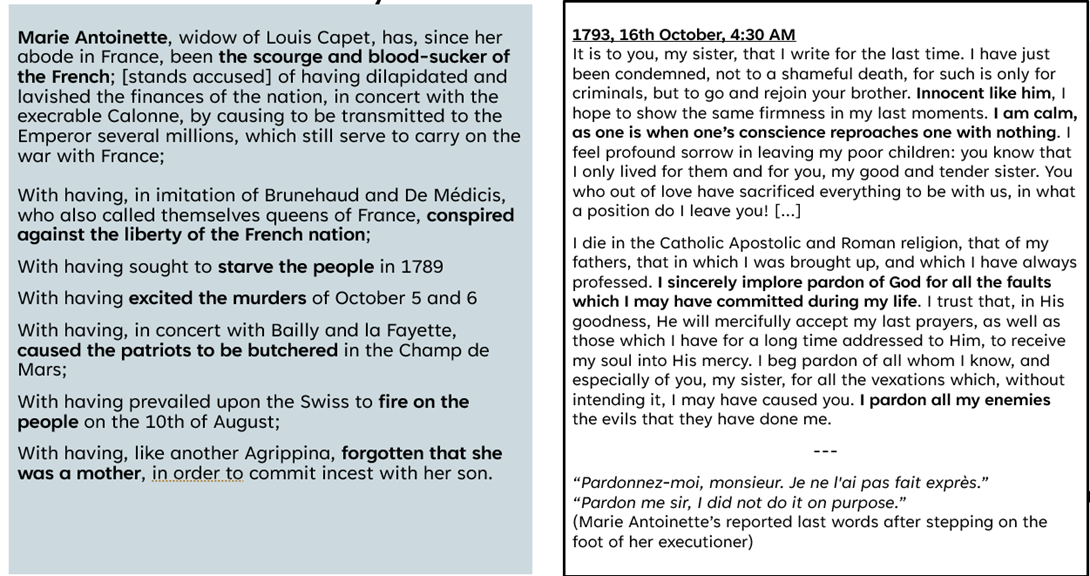

Here we have a primary source from the life of Marie Antoinette. This is a denouncement where we read that she has been accused by revolutionaries as: The scourge and blood sucker of the French people, has conspired against the liberty of the French nation, has starved the people, has excited murders of various kinds, and had irregular relations with her son (Doyle, 2018).

We can then contrast this to the picture she paints of herself in her last letter to her sister-in-law, where she asserts: To be calm and feel no shame because she is not a criminal, sorry for leaving her family, implores God’s pardon for her faults, and pardons her enemies (Antoinette, 1793/2011).

In another piece of primary evidence, she apologises to her executioner upon stepping on his foot (Britannica, 2023).

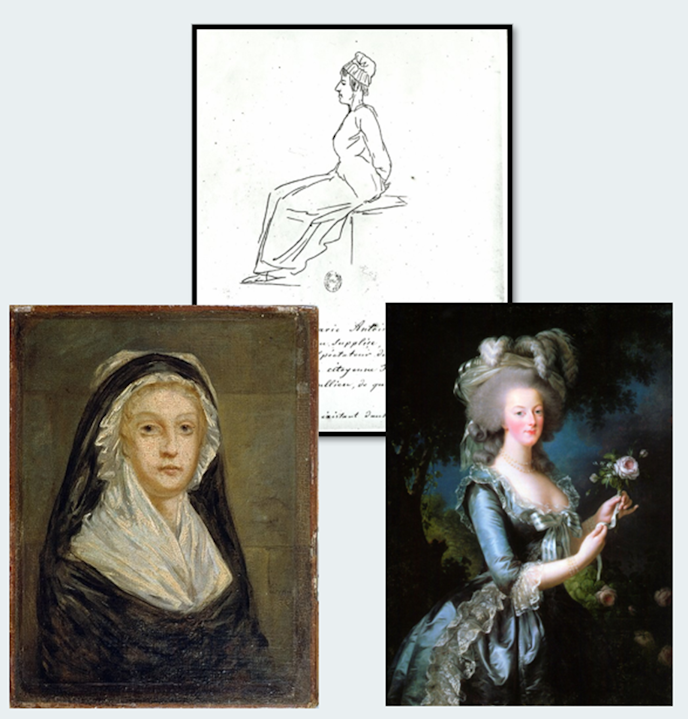

The experience for a student, in navigating these two differing accounts, cannot be replicated by a summary from a textbook or from Wikipedia. To tie back to picture studies, you could also do this with paintings. Below is a sketch of Marie Antoinette on her way to her execution, a portrait painted when she was imprisoned, and a portrait before she was imprisoned.

Classic Texts vs Contemporary Slop

This is analogous to the use of Classical texts as well. Against the use of classical texts are what I call contemporary slop texts.

I think one of the best expressions of what makes something classical is by the German philosopher Hans-Georg Gadamer, who paints the classic as significant precisely because it is ever relevant without pandering to the present; it is truly remarkable because of its dynamism, not because it’s a sluggish, immovable monument (Gadamer, 1989).

What we find in the case of contemporary slop is a text that is smoothed out beforehand; there is a conclusion safely in sight. It might be slightly harsh to call Tim Winton’s Blueback slop, but it is boring because it is an uncomplicated story of a small family saving the local environment from a colonising destructive corporation – we know in the end that family and love will win. The students know this too. They know nothing is really in play (Winton, 1997).

Contrast that with The Tempest, where one could try to form an analogy to make Prospero a colonist but suddenly find your own criteria questioned by the text because Caliban is far from a noble savage. If we are honest, we will find that we cannot make such an analogy because these classic stories are odd, the characters are odd; they do not fit neatly in a box. They are striking – they rouse intellectual and emotional energy. And if they are difficult, let us not forget that the difficulty is the education (Shakespeare, 1611/2008).

So in short, I would encourage teachers to enter into this great conversation, to choose texts that are not smoothed over, that are pandering, but choosing texts that are weird and wonderful, that generations have pondered over, texts that are so distant but closer to the heart than you could imagine—and moderate that dialogue with the virtues of courage and humility.

With courage, to speak and interpret the text,

And with humility, to listen to the text even when it does not match your preconceptions.

I hope the three techniques we’ve walked through in this article: Picture Studies, Class Catechisms, and Choosing Classic Texts, will help bring your students to sense a transcendence beyond the material demands of life, to see harmony in their lives and their world, and to join in with the Great Conversation.

___________________________________________________________________________________________

References

Antoinette, M. (1793/2011). Last letter to her sister-in-law. Nobility.org. https://nobility.org/2011/10/last-letter-of-marie-antoinette/

Boethius. (n.d.). Consolation of Philosophy (V. E. Watts, Trans.). Penguin Classics.

Boethius. (n.d.). De institutione musica (H. F. Stewart, H. B. Workman, & T. A. Sinclair, Trans.). Harvard University Press.

Britannica. (2023). Marie Antoinette. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Marie-Antoinette-queen-of-France

Caldecott, S. (2011). Beauty for truth’s sake: On the re-enchantment of education. Brazos Press.

Gadamer, H.-G. (1989). Truth and method (2nd rev. ed., J. Weinsheimer & D. G. Marshall, Trans.). Continuum.

Gibbs, J. (2019). Something they will not forget. Gibbs Classical.

Gibbs, J. (2020). Love what lasts: How to grow deeply rooted and emotionally mature children. Gibbs Classical.

Glass, K. (2019). Consider this: Charlotte Mason and the classical tradition. Classical Academic Press.

Hicks, A. (2021). Composing the world: Harmony in the medieval Platonic cosmos. Oxford University Press.

Marie Antoinette in revolutionary pamphlets. (n.d.). Academia.edu. https://www.academia.edu/109704752/Marie_antoinette_in_Pamphlets

Pennick, N. (1992). Sacred geometry: Philosophy and practice. Thames & Hudson.

Pieper, J. (1998). Only the lover sings: Art and contemplation. Ignatius Press.

Shakespeare, W. (1611/2008). The tempest (B. A. Mowat & P. Werstine, Eds.). Simon & Schuster.

Walker, D. P. (1993). The harmony of the spheres: A source book of the Pythagorean tradition in music. Dover Publications.

Winton, T. (1997). Blueback. Pan Macmillan.